Stone Mountain

Commemorative Half Dollar

History

There are so many conflicting stories surrounding the concept, formation, carving events, sculptors, and individuals involved in the creation of the Stone Mountain Memorial that one must read a tremendous amount of material and sort out for oneself what to believe. No matter what the events prove to be, the result was the creation of the largest relief carving in the world, and a commemorative coin used in the fundraising for that effort.

Our goal is to study the Stone Mountain Half Dollar and to put it in the perspective of the time. We must touch on events surrounding its creation, but we are not here to argue the efficacy of the war nor its aftermath. There are plenty of web sites, message boards, and other ways to express those opinions. We are studying the only the numismatic aspect of the coin and its creation. However, in many ways the coin and the carving are inextricably linked.

Historical Context

While creation of the Stone Mountain Memorial might seem unusual or inappropriate to us today, there are some important historical things to consider and how different our world was in 1909.

In 1909 the close of the Civil War was only 44 years past. To put that in perspective that is less passage of time than we are today from World War II, and those memories are still fresh in our minds. By some accounts, the South mobilized as many as eighty percent of the fighting age male population in the war effort. So it would have been impossible to avoid being touched by the war through some family member or associate. Many veterans were still living and there was tangible evidence of their sacrifice in a losing cause every day. To those who lost family members, the war was still a tangible thing not a distant historical event. We must also remember that Reconstruction, and therefore occupation, had ended in 1879, just 30 years earlier. While needed to restore the Union, it too prolonged the war in the minds of many in the South.

In the North passions ran just as high, and for similar reasons. Many had loved ones who died in the conflict and there were tangible signs of the war in its people and in some cases, in places.

Genesis of the Idea

By some accounts the concept of the Stone Mountain carving honoring the soldiers who fought for the South during the Civil War began with one person, Mrs. Helen Plane of Atlanta who had lost her husband in the war. Whatever the genesis of the idea, it is obvious that the idea was taken up by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and advanced by discussions with Gutzon Borglum in 1915.

But no matter who originated the idea it was dwarfed by the conceptual carving as expressed by Borglum. The original concept of the UDC was a twenty by twenty foot bust of the head of Robert E. Lee on the side of the mountain. Borglum correctly recognized that such a memorial would be dwarfed by the size of the mountain. At 867 feet tall, over a mile wide, and with a circumference of seven miles, Stone Mountain is one of the largest granite outcrops in the world.

But no matter who originated the idea it was dwarfed by the conceptual carving as expressed by Borglum. The original concept of the UDC was a twenty by twenty foot bust of the head of Robert E. Lee on the side of the mountain. Borglum correctly recognized that such a memorial would be dwarfed by the size of the mountain. At 867 feet tall, over a mile wide, and with a circumference of seven miles, Stone Mountain is one of the largest granite outcrops in the world.

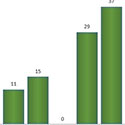

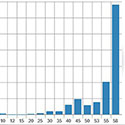

But Borglum's concept was well beyond anything that could be funded. He conceived a carving that would be 1,200 feet wide and would show between 800 and 1,200 soldiers. He also envisioned a Memorial Hall that would be 320 feet by 60 feet. Much like Petra, it was to be carved entirely into the mountain and only a bronze door would be other than stone. The memorial hall had a secondary purpose of preserving the names of all the contributors to the work, a roster of all Confederate soldiers, and a chance for major contributors to have their names carved on the walls. If this were not enough, Borglum also planned to build the world's largest amphitheater in front of the memorial hall. Dreaming big was not a problem, but execution of this plan was financially and practically impossible. The UDC campaign envisioned raising $8 million from donations and sales. This was probably a more practical cost figure, but unattainable. The sales goals were broken down as follows:

- 1,000 enrollments of $5,000 each

- 2,000 enrollments of $1,000 each

- 1,000,000 enrollments from the children's founder's roll at $1.00 each

Notice that the coin sales were not included in this initial concept, so we might assume that sales shortfalls helped foster the concept of the commemorative coin.

Once the UDC and Borglum agreed on design and accepted the challenge of creating the memorial, the need for funding was born and it is from this event that the Stone Mountain Half Dollar was created. Without the carving and the need for funding there is no coin to collect and study.

World War I

Just as the UDC and Gutzon Borglum were getting started, World War I intervened and halted all progress. Perhaps an even more difficult issue was a loss of momentum and wasted cost from starting and stopping the project. Management of a project of this size was in all likelihood beyond the local UDC chapter because of lack of experience, not enthusiasm or commitment. The end of the war and the return to a more normal economic environment served as a catalyst to restart the project.

First Failure

There was a vigorous campaign launched to raise money but it became obvious that much more would be needed as most efforts were failing. From these struggles the idea to create and sell the commemorative half dollars was born. Conceptually, corporations would purchase large quantities of the coins as a promotion. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Coca-Cola, the Southern Fireman's Fund Insurance Company, and several banks were among the sponsors. But the fundraising goals of the UDC were totally unreasonable given the economic times sandwiched between World War I and the Great Depression.

But it was the very public disagreement between the SMCMA and Gutzon Borglum that helped doom the first project and sales of the coins lagged expectations. Other contributions faded as the very public fight tarnished the project and reputations of all involved. Mixed in with all this, and a catalyst for the Borglum conflicts, was the discovery that the association's president had spent lavishly on his personal needs and less on the intended carving. While these revelations vindicated Borglum and explained his concerns, they did not come in time to avoid the very public battle that so damaged the project.

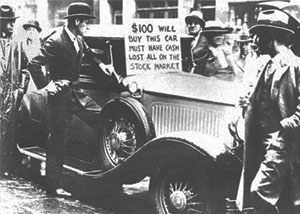

Great Depression

The Great Depression halted many activities in the 1930s, but there was a World's Fair in Chicago in 1933. The State of Georgia was still offering the coins in its exhibit for the customary $1.00 fee. But selling coins at this exhibit would not fund the massive effort in the face of disastrous economic times.

The Great Depression halted many activities in the 1930s, but there was a World's Fair in Chicago in 1933. The State of Georgia was still offering the coins in its exhibit for the customary $1.00 fee. But selling coins at this exhibit would not fund the massive effort in the face of disastrous economic times.

Augustus Lukeman who took over once Borglum departed did much to move the carving along, but in 1928 the land and unfinished carving reverted to the original owners. Nothing could have saved the project in the face of the Great Depression. In Georgia there were bank failures, of course the stock market decline, and job losses. Georgia had a large agrarian population and there was little if any money for projects of this nature.

So all work went dormant for decades. The failure of the SMCMA and return of the land to the original owners seemed to spell the end of a well intended but poorly conceived project.

Dormant Years

In a strange twist of fate many wanted Borglum to return to finish the carving after his success at Mount Rushmore, and he agreed to do so. But little work was done and when he passed away in 1941 before any serious work could be done. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation actually volunteered to loan $1,250,000 toward the project, but again no progress was made.

From the Great Depression through the early 1960s many residents of Georgia passed by the partial carving on the mountain and probably thought it would never be restarted or finished. It just looked to be too big, too difficult, and too expensive. It became an unintended monument to failure.

From the Great Depression through the early 1960s many residents of Georgia passed by the partial carving on the mountain and probably thought it would never be restarted or finished. It just looked to be too big, too difficult, and too expensive. It became an unintended monument to failure.

One of the monument's intended selling points also became an Achilles heel. The monument faced U. S. Highway 78, a major thoroughfare to Atlanta from many destinations east of the city. So all commuters had a view of the failed effort twice a day. The carving became somewhat of an eyesore and the State was probably faced with a decision to either finish it or destroy it. Given the expenditure of effort and money, destroying the monument would have seemed impractical.

Final Push

If there is any practical lesson from the Stone Mountain Memorial project it is that vision and enthusiasm are great, but it also takes cooperation, management expertise, and serious funding. We only know of one project of this type ever attempted with private funds, the Crazy Horse Memorial, and it has become a multi-generational project that could last from 75 to 100 years.

But with the Stone Mountain Memorial there was no continuity from stage to stage. Without the State of Georgia stepping in to take over the project it might still be incomplete. In 1958 the State of Georgia purchased the mountain and 3,200 acres of surrounding land for the purpose of building a State park. In 1960 a contest was held to pick a new sculptor for the project and Walker Hancock was chosen for the job in 1963. Ultimately Hancock paired up with welder Roy Faulkner and the two finished the sculpture. A dedication ceremony was held on May 9, 1970 and the sculpture was declared complete.

Looking back Borglum receives a lot of credit for his vision and believing a sculpture of this magnitude could even be attempted. Even though scaled back from his original design, it is still the largest relief in the world. What we see today is the work done by Lukeman, Hancock, and Faulkner. In our eyes Roy Faulkner is the hero in the carving story. Visions are always needed for inspiration, but ultimately it is execution that is needed. His innovations with the carving torch and ability to see what others could not see was the ultimate success story. Perhaps this is fitting since he was more of a "foot soldier" than a general.

For More Information

There is no shortage of opinion on the coin and the surrounding story. By far the best study of the events we have read was by David B. Freeman in his book "Carved in Stone, The History of Stone Mountain." We would recommend this study to anyone interested in the coin and surrounding events. But for a full understanding it is necessary to read whatever you can find and perhaps piece your own story together.

Legal Stuff

Home

History

Our Collection

Exonumia

The Coin

Original Design

Modifications

Grading

Price Guide

The Carvers

Contact Us

The Carving

Coins by Grade

Sources

Commemoratives

Statistics

Variations

Final Design Issues

Production

Harvest Campaign

Copyright (c) Georgia 1832,LLLP 2018-2018